When I was in my mid-teens, I bought a small hand-operated printing press. The Kelsey Press could print business cards and post cards, and it came with a collection of letters you could place by hand in a frame. You had to set the type in a reverse mirror image arrangement. When you pressed the big handle down, the ink roller would move up to the platen to get some ink, then it would roll back down over the reverse type to deposit ink on the raised surfaces. The paper to be printed would then be raised up and pressed against the inked type, and you would instantly have a printed page. Do this 500 times and you would have 500 printed pages and a sore arm.

Typewriters at that time were pretty efficient, and I had my share of manual typewriters, brands like Underwood and Smith Carona. I still remember the day I first used an IBM Selectric. I was mesmerized by the clean crisp type made by that moving carbon ribbon and the acrobatic sphere with the letters protruding out of it, spinning first one way and then the other, pouncing into place against the paper and leaving its mark. It was amazing to watch a Selectric do its thing.

Moving on, a few years later, computers would be invented, used first by businesses, then brought out in a consumer version that was purchased by a few brave souls for experimentation purposes. This was the next big advance for printing. The first thing I bought that even remotely resembled a computer was a "character generator" that would create letters and words on a TV screen. It was basically just a keyboard that hooked up to your TV set's antenna connections. It was a load of fun (almost magical) to type a word on the keyboard and have it appear on the TV screen, in any of several different colors and sizes.

From there was a succession of simple processors and printers, among them the Texas Instruments version of the home computer, a TI-99. An interesting entry-level device, it was followed by the VIC-20 by Commodore. If so inclined, someone could learn the BASIC computer programming language and write their own programs.

While I enjoyed the VIC-20 with its audio cassette player that doubled as a storage device for software programs, I never did move up to the Commodore 64, a more advanced model. The word processing capabilities of these early computers were quite remarkable, when compared with a standard typewriter. Hook them up to a dot-matrix printer and stand back.

The difference that was most noticeable was in the ability to correct mistakes, which on the computer was a backspace, backspace, and on the typewriter was the application of sticky Liquid Paper or backspace,backspace through a correction ribbon, then type what you meant to type in the first place. If you were making two or three carbon copies at the same time, good luck.

In college I had access to ditto machines and mimeograph machines, both of which made copying short runs of typewritten material easier and faster, if you could withstand the smell of the fluids they consumed. The other day I tried to describe the smell of duplicating fluid to someone, and it was impossible. The smell was just that unique and distinctive.

In the early 1970's, when I became a newspaper reporter, newspapers had transitioned from linotype hot lead typesetting to justiwriters, where one would type on a keyboard and holes would be punched in a long paper tape. Each row of holes across the paper tape would represent a letter, number or punctuation mark. The long punched paper tape would then be loaded into the justiwriter printer, which would read the punched holes on the tape, adjust the spaces in-between the letters, and then produce justified text columns. These would then be trimmed and pasted down on a layout page. A tremendous amount of engineering went into producing newspaper text columns that were justified (lined up evenly) on both sides.

The justiwriter gave way to the Compugraphic, a much faster and more computerized process. It consisted of a huge computer with a drum around which different plastic strips would be wrapped and secured. Each of these strips featured a different type font. Punched paper tapes would be loaded in the front, the drum would spin rapidly, with flickers of light shining through the film strips at just the right time to "print" a letter. The justified text columns would slide slowly out of a processor developing unit, much like film being developed. These advancements were great for justified columns of text, but display advertisements still had to be pieced together using elements clipped from huge clip art books.

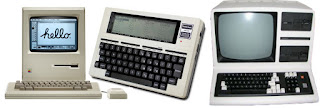

However, in the early 1980's, I began using an Apple Macintosh to generate display ads. It printed out display advertisements so clearly and quickly it was almost a miracle. Home use of these new fangled computers was one thing, but for newspaper composition rooms across the nation, they soon became indispensable.

Sometime during those years, I had fun with a Radio Shack (Tandy Corporation) Model 100 portable word processor, and, later, a Tandy Model 4. I will never forget Radio Shack's wonderful Deskmate Graphical User Interface, which beat both Mac and Microsoft in the functional utility department. The Deskmate home screen featured from six to eight squares, each square representing a software program you used frequently. Within each square was a list of files you had recently worked on. So if you wanted to go back to a file you had already created, all you had to do was CLICK on the name of that file inside the square, and the software would launch and bring to the screen the file you wanted. What a convenience. As far as usability, I haven't liked many GUI's as much as I liked Deskmate.

Then came the keyboards that actually created digitized word processing documents that were stored on floppy disks. The five inch disks which were actually "floppy" faded fast, and they were soon replaced by the 3.5 inch disks which were housed in hard plastic cases. Those were still called floppy disks for some reason.

After that it is a blur. Storage devices ballooned in storage capacity, there were ZIP drives, then finally came the mega-giga capacity of CD-rom disks and USB flashdrives. You can now store enough word processing documents on one external drive to contain the entire Library of Congress. (That may be an exaggeration, but then again, maybe not.)

Microsoft Windows and Apple Macs are now the industry leaders, but it's a shame that the forerunners in the computer business (Texas Instruments, Xerox, and Tandy) were not able to maintain their early leads. Even today's software doesn't seem to be as useful and user friendly as the early word processing, spreadsheet and database programs.

I loved early versions of Photoshop image editing, Filemaker Pro database creation and management, and Sound Blaster audio editing software, but it almost seems today that they are too gigantic, too complex, and too feature-rich to just do the simple things you need them to do. Not everyone feels that way, but I am remembering the days when each program did one thing and did it well. You may still use Powerpoint for straight-forward slide after slide text displays, but it can do so many other things it is astounding.

I suppose astounding is the best word for how the technology for printing text has evolved over the past 50 years, from setting type by hand to pushing the button on an ink jet or laser printer; from pasting down a halftone photograph on a layout page to tweaking a picture pixel by pixel in Photoshop for printing out at 600 dpi. It's changed mightily and quickly, almost too quickly to keep up. But I tried, and enjoyed ever minute of it.